“…You might say I ain’t free. It don’t worry me…”

Last night I watched the great Robert Altman film “Nashville”. I hadn’t seen it since 1975 when it was released, and I was struck by how amazingly well it holds up and how relevant it is in the Age of Trump. (FYI, it has little or no relation to the recent TV series, other than the title.)

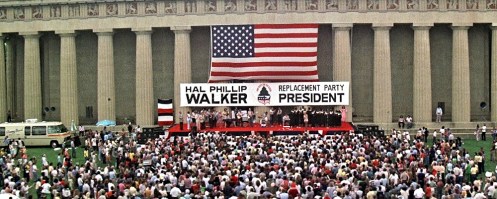

For those too young to have seen it, “Nashville” takes place over the course of five days during which the lives of more than 20 major characters–all in some way linked by the city’s country music scene–intertwine and reach a stunning climax. The story is framed by the campaign of an alternative presidential candidate named Hal Phillip Walker, who is never seen in the movie.

The film is not overtly political, certainly not in a partisan sense. However, viewing it now it’s impossible not to find in the unseen Walker character a precursor for Trump. His message is not identical, but his methods and appeal are the same–the manipulation of resentments fueled by radical changes in American society. It’s like watching the early stages of this country’s cultural and political divide into two hostile tribes.

The film was made in a time of national turmoil, eerily similar to today. The movie was shot on location from July to September 1974, and Nixon resigned over the Watergate scandal on August 8 of that year. The assassinations of John and Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. were still fresh in everyone’s minds, and the country was still riven over the Vietnam War. Echoes of all of these emerge in the film, though they are not really central to the story. Other national issues such as racism, religion, and violence in our society are also touched upon. And, of course, celebrity worship and the pursuit of fame.

But I think the most important theme is the political co-optation of the country music industry and the sub-culture in which it thrives.

To me the most interesting aspect of the movie is the light it sheds on role of country music (which had only recently started going by that name, as opposed to “hillbilly” music) in creating a false nostalgic mythology of the “real America”. You know–rural, white, Protestant evangelical and filled with loving, hard-working families living hard-scrabble but fiercely independent lives. This was the meme seized upon by Nixon as “the silent majority” back then and which has become the fundamental gut appeal of the Republican Party. We see it manifested today in the resurgent White Nationalist movement and Trump’s anti-immigrant campaign.

Of course, this rosy-colored musical vision was bogus then and is even more so now. What began as a genre authentically rooted in Appalachian culture, had become by the 1970s a slickly formulaic money-making machine whose style and content was tightly controlled by the Grand Ol’ Opry and the Nashville recording studios. The Opry itself had decamped from the church-like downtown Ryman Auditorium to snazzy new digs in suburban Opryland, which then morphed into a theme park. Nashville country music was on its way to becoming what it is today, Vegas with a southern accent.

The movie subtly satirizes the various country song formulas with lyrics that deftly hit all the requisite notes–sometimes hilariously. Many of the songs were written and performed by cast members, none of whom were professional musicians, let alone country musicians. Some of them are actually pretty good–one won the Oscar that year. Some are sly parodies, but just close enough that they could almost pass for the real thing. (The movie includes more than a hour of performed music.)

Ironically, in the early ’70s there was a rebellion among some country singers against the Nashville straight jacket–a movement that became known as “outlaw country” led by performers like Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, and Kris Kristofferson. This was actually what put Austin on the musical map as artists shed their Nudie suits and turned their backs on the Grand Ol’ Opry and headed for the Armadillo World Headquarters. This turned into something of a cultural/political divide as well, with Willie Nelson famously smoking massive amounts of weed, while Merle Haggard claimed that “we don’t smoke marijuana in Muskogee.” The film barely touches on all of this, but it does give a brief nod to the fact that some non-country artists were coming to Nashville to record with local musicians, as Bob Dylan did in 1969 with “Nashville Skyline”. It was complicated.

All of that is now ancient history. The Nashville establishment had its counter-reformation and re-invented itself as Glam Country, with elaborate stage productions, fancy arrangements, and fabulous clothes, hair, and makeup for female artists. (The cowboy hat became de rigueur for male artists–something almost never seen outside of Texas or Oklahoma before the 70s.) The women became Hollywood-style divas, while the men had to project that scruffy, bad boy vibe. The song lyrics kept pretty much to the same themes (although with more sexuality), but the packaging was very different. The lyrics said: “Your lives may be crappy, but you’re the real Americans.” The production values said: “Wouldn’t you like to be rich like me?!”

The conservative political orthodoxy of country music also stuck and hardened. And woe betide the country artist who dared buck the party line, as Natalie Maines of Dixie Chicks discovered when she declared in a London concert in 2003: “We don’t want this war, this violence, and we’re ashamed that the President of the United States is from Texas”. Suddenly, the group was being denounced on talk shows, they were being boycotted, their CDs were ceremonially destroyed in public protests, and they were blacklisted by corporate broadcasting networks. Country music had become the official soundtrack of red state America, which it remains today.

Maybe they didn’t smoke pot in places like Muskogee in 1974, but they’ve sure graduated from white lightnin’ to crystal meth, Oxycontin, and smack now. Rural America–the stronghold of country music–is in sad shape, and the people who live there are angry, resentful, isolated, and susceptible to manipulation by a demagogue who knows how to press their buttons. Country music, with its defensive and often belligerent edge, plays right along.

There is a song in “Nashville” that is threaded throughout the complex story, but which becomes central at the climax of the film. The refrain goes:

It don’t worry me.

It don’t worry me.

You might say I ain’t free,

But it don’t worry me.

That could be the theme song for Trump supporters.

[Note: Robert Altman’s “Nashville” is available on Amazon Prime. Of course.]

I’ve just finished watching Nashville for the 3rd or 4th time since trumps presidency and the film just seems to grow more and more relevant as culture, industry and politics keep blending into each other. Really interesting read, as a youngen and one not even from America I honestly had no clue about country music’s confused beginnings. That really gives a new perspective on the film.

Anyway keep safe, let’s hope the worst is soon over.